Whose auntie died? Auntie literature defined, explained, venerated.

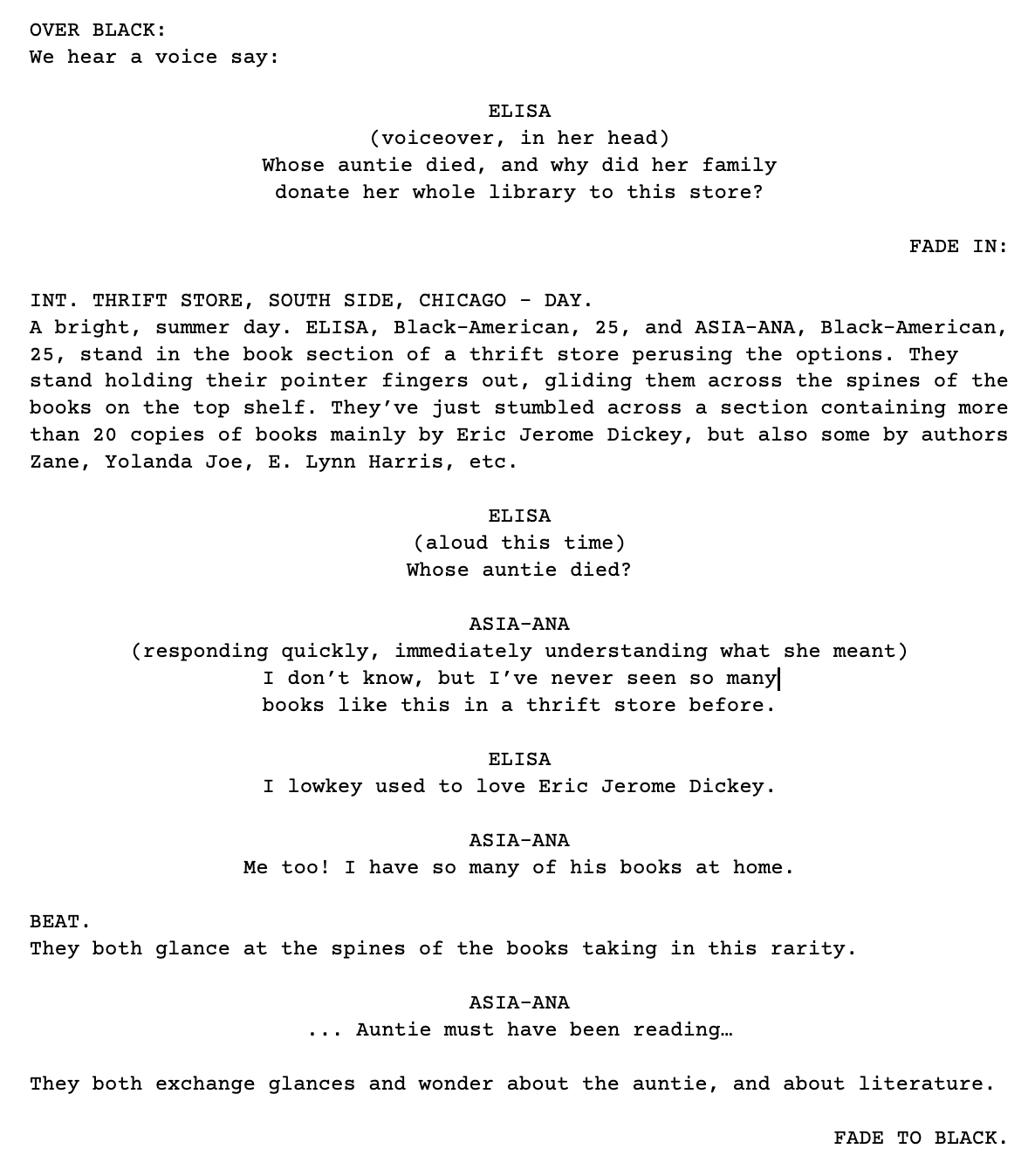

A glimpse into the moment that the term “auntie literature” emerged into my vocabulary.

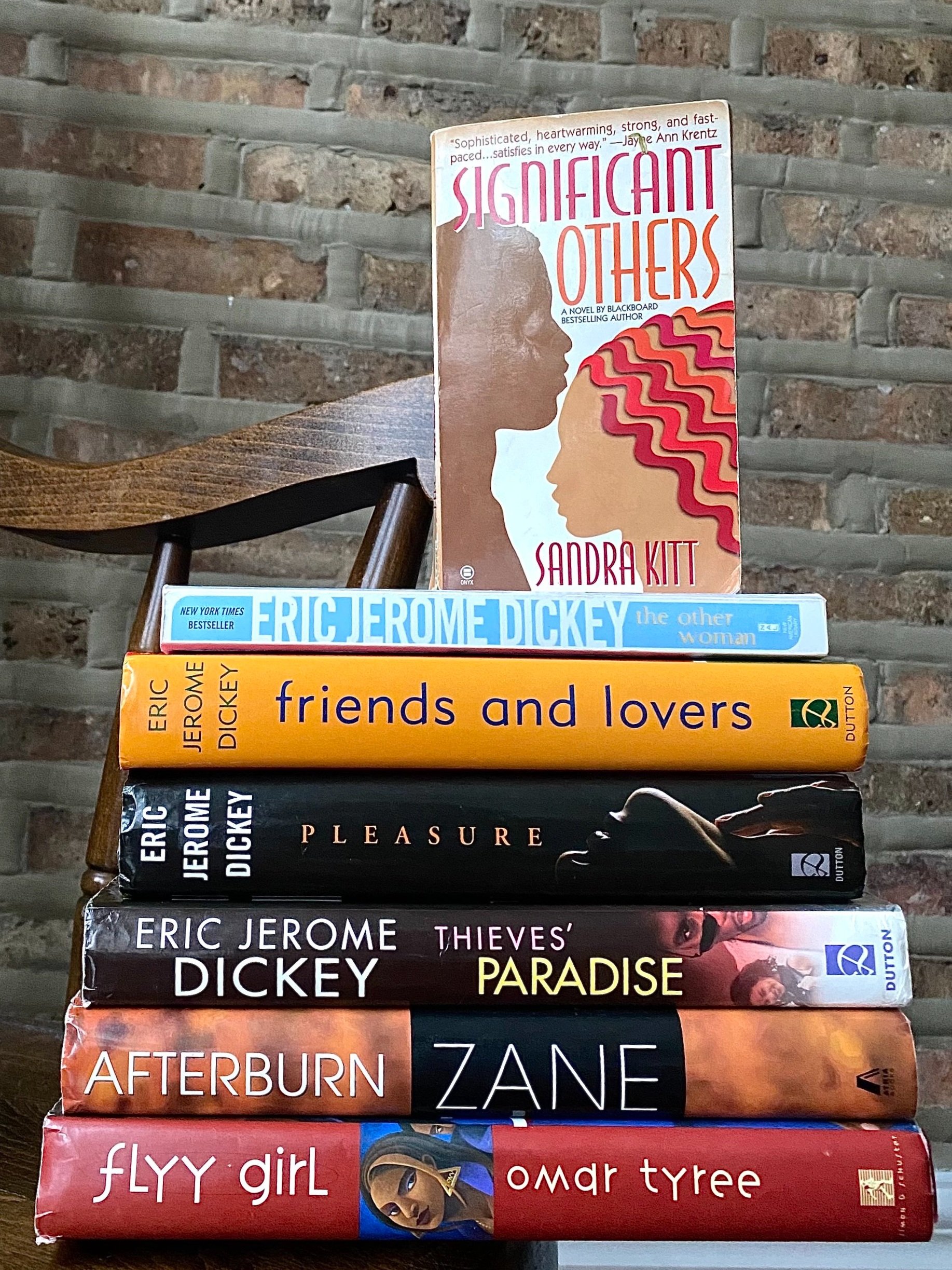

“Whose auntie died?”

For two decades, I’ve had a living, breathing relationship with reading. I grew up in a very traditional household where my parents were racing against the technological clock all while trying to raise my brother and I with some semblance of the childhood they’d experienced. Notably, they created a set of rules we had to abide by - the biggest being a rule that prevented us from watching TV during the week. For me, this regulation meant that I had all of the time in the world to fellowship with the characters in the stories in which I’d been introduced, and that I could read to my heart’s content. But by the time I became a middle-schooler, I was feeling like childhood was a bit too slippery to hold onto anymore, and that my typical stories were no longer “enough” for my needs. My adolescence had snuck up on me, in the mid-2000’s, and I couldn’t shake off the fact that I was searching for more.

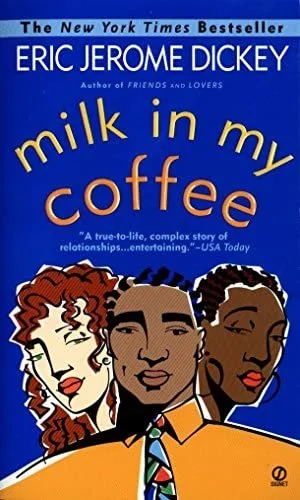

I first discovered Eric Jerome Dickey, among others, during this transitional period. I was around 11 or 12 years old in 2008 when I found a book tucked into the bottom-left hand side of my parents bookshelves. I remember the smallness and the bigness of the first Dickey book that I picked up. It fit into my hands easily, but it was thicker than anything I’d really gotten into thus far. The cover featured a funky illustration of what appeared to be a Black man, a Black woman, and a white woman, and the title Milk in My Coffee (1998) had me interested. I remember being immersed in the story, and being overwhelmingly drawn into these characters as they sifted through layers of their experiences in relationshipping. I was maybe too young to catch the nuance for real, and likely too young to be exposed to the eroticism strewn throughout the pages. In the end, though, what was opened up to me was a world where Black characters were written honestly and openly, in love and in conflict.

After this introduction, I discovered more books like Milk in my Coffee that provided me with even more layers of Black-American life to hold on to. From Dickey, I then discovered Zane (Afterburn, 2005). From Zane, I then discovered E. Lynn Harris (Invisible Life, 1991). And from Harris, I then discovered Sister Souljah (The Coldest Winter Ever, 2006) and Teri Woods (True To The Game, 1999). I soon began to realize that maybe it wasn’t the most normal experience to be 12 and be well-versed in this type of literature. I mean, what even was this type of literature? It was different than those series featuring Black-American high school experiences, it was different than the classic Black-American texts being discussed at large - the Morrison, the Hurston, the Baldwin. But what was exactly would we even call it?

Standing in the book section of the thrift store that day (as referenced in the short screenplay above), this question - “Whose auntie died?” - came naturally into the conversation between my best friend and I. When thrifting, even in Chicago, it was rare to find more than a handful of books by Black-American authors. And to find more than 10, 20, 30 of these texts by Dickey, Harris, Zane and more all stacked right next to each other? The implication was that somebody’s auntie had transitioned from this world, because who with such a robust collection of these types of novels would simply give them away en mass, at random? And it was then that I was given the answer to the questions surrounding the name for this type of literature.

“…auntie must have been reading reading…”

In the homes of many Black women you will find - nudged into bookshelves, laying on bed-side tables, resting on the floor by the bed, squeezed underneath couch cushions and mattresses, resting in literary holding spaces - stories that tell the tales of lives as they’re lived. And inside of these stories, you will discover tales of intimacy, eroticism, and sexuality. These stories are not always revered as classical Black literature, maybe because of the heavy erotic overtones, maybe because of the storylines being outlined. I mean, when a book is blurbed* as “a true-to-life, complex story of relationships…entertaining” (the blurb on the cover of Milk in My Coffee) one is not naturally inclined to believe that they’re reading the next literary great. But these stories, authors, and arcs, have been heralded as precious by aunties across the United States. And these stories just may be the literary greats that go unsung.

Right now, in Black-American culture, the colloquial term “auntie” adorns Black women of a certain age. Whereas “auntie” has a history of heaviness and belittlement, young Black-Americans now utilize the term to reference an experienced loved one who keeps it real, and is dearly beloved. Imani Perry, in “What Black Women Hear When They Hear ‘Auntie’ for The Atlantic writes about the sticky, tricky public discourse regarding the term: “Auntie is a word that comes with baggage, and young Black people calling Black women over 40 years old “Auntie” in the public arena are not carrying that baggage. An “auntie” in popular parlance is defined by being independent, attractive, and powerful.” (The Atlantic)

What I mean when I label something as relating to “aunties,” is that this ‘something’ is enjoyed by those women in the family who have a level of freedom of access and movement that creates joy within themselves and joy within those around them. Auntie is fly, she’s untethered, she’s abundant, she’s free. And Auntie reads with a fervor, and what she reads better give her something to hold on to - be it a nugget, a book husband, or a deep belly laugh.

And thus, Auntie literature can be used to describe a type of fiction centering Black Diasporic experiences, namely focusing on love and the erotic. Auntie literature does not need to be explained or defined in a way that creates a polished, top coat that reflects the deeper layers of meaning stitched into the fabric of their stories. Auntie literature is bold in its clarity. The language is accessible, the themes are universal, and the eroticism is spicy enough to give you something to desire and dream about. Auntie Literature also typically contains storylines of love and lust, heartbreak and betrayal, of friendship and community. Where would we be without auntie literature? I certainly wouldn’t be as exposed to Black-American life, to dating, to heartbreak, to friendship, to family, to redemption, to loss, to grief, to love.

It’s only my hope that the conversation surrounding auntie literature continues to grow and evolve as the digital space creates avenues for communities to express veneration for different types of literature. There’s a surge of Black readers and content creators who pursue Black romance of all genres, paying special attention to urban fiction and Black erotica. And somewhere nudged in the in-between are those readers who navigate spaces meant for the aunties - as a new generation of aunties themselves rises from the ground up. And it’s my hope that we only grow to continue to make space for the Dickey’s, the Zane’s, the Hariss’ to be known and held as complex and true.

Interested in getting into auntie literature, but don’t know where to start? Try any of these:

Eric Jerome Dickey: Milk in My Coffee — The Other Woman — Friends and Lovers — Sister, Sister — Pleasure

Zane: Afterburn — Nervous — Addicted — The Sex Chronicles: Shattering the Myth

E. Lynn Harris: Invisible Life — Just As I Am — A Love of My Own

Terry McMillan: Disappearing Acts — How Stella Got Her Groove Back — Waiting to Exhale

Carl Weber: Big Girls Do Cry — The Man in 3B — Married Man

Geneva Holiday: Fever — Lover Man — Heat